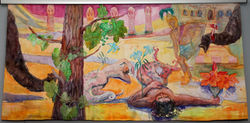

Salammbô. Le royaume perdu/

Salammbô. The Lost Kingdom

The exhibition at Andreja Upīša Memorial museum was dedicated to French novelist Gustav Flaubert (1821-1880) on his 200th anniversary. The body of work was inspired by Flaubert's historical novel "Salammbô" while honoring the memory of Andrejs Upīts, the author of the novel's outstanding Latvian translation.

Curator of the exhibition: Ilze Andresone

Photos from the exhibition: Ivars Puķe

Photo from studio: Velta Emilija Platupe

"C'était à Mégara, faubourg de Carthage, dans les jardins d'Hamilcar …"

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |

C H A R T A G E

“It was a huge city.

It had 60 towers, 6000 temples, of which 3000 were of marble, 2000 of porphyry, 600 of alabaster, 300 of jasper, 50 of plaster, 45 of ivory, four of silver and one of gold. The streets were 300 feet wide. They were paved with marble and covered with a layer of silver. Scented lamps were burning near the houses, white elephants were walking around the streets, surrounded by singers and dancers. The air was so fragrant and the atmosphere so harmonious that flowers and birds never died there. Carthage possessed 3,000 ships, 600 fortresses, 100,000 horses, 12,000 elephants, 100 million talents a year, and Hannibal…”

/"Rīgas Laiks", August 2021/

We know little about ancient Carthage - the great power of North Africa, the ruler of the Mediterranean, as well as its capital, the ruins of which can be found on the territory of modern Tunisia. The only written sources have been left to historians by its enemies: Jews, Greeks and Romans. The latter, having lived for a long time under the slogan "Carthage must be destroyed", finally did it by winning the Third Punic War in 146 BC. The city burned in flames for seventeen days, after which the victors, as they say, plowed up the ruins and soiled the ground with salt so that nothing live could grow there. Later, Carthage lives in the memories of Western Europe, gradually turning into the mysterious, legendary,rumored Eastern Land, the defeated rival, which inspires admiration, envy, and horror even after it's death.

We do not know how far we can believe the testimony of Carthage's enemies. Modern archaeologists are debating whether living people, including children, were really sacrificed to the Carthaginian gods - finds in the excavations allow different versions. We can only guess how exactly Carthage's "barbaric" luxury manifested itself and to what extent we can believe in eternal flowers and eternally singing birds.

Perhaps if we knew more, Carthage would inspire us less.

The great French writer Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), whose 200th anniversary is celebrated on 2021, also goes to Carthage to seek refuge - in this case from the uproar caused by his previous novel "Madame Bovary". Flaubert travels around North Africa, thoroughly gets to know the testimonies of historians, orientalists and archaeologists of his time; more than four years of studies culminate in a novel centered on the mercenary revolt in Carthage (240-238 AD) between the First and Second Punic Wars, as well as the femme fatale, the warlord Hamilcar Barca's (died around 228 AD) daughter Salammbô, priestess of the goddess Tanita. An inextricable tangle of passions is intertwined around her.

Salammbô is a figment of Flaubert's imagination (sources say that Hamilcar had a daughter, maybe even two or three, but neither their names nor their life stories are yet known to us). Flaubert endowed her with youth, beauty, a little mystical exaltation and almost desperate courage. The lust inspired by Salammbô leads the rebel leader Matho to go conquer Carthage and die an agonizing death at the end of the novel. Erotic passions merge with political and religious ones in the novel; brave warriors, passionate lovers and wise priests inhabit a space where the sacred is indistinguishable from the profane. Here there are both cruel battles and torture of enemies, as well as insanely magnificent feasts; here children are sacrificed to Moloch and songs of praise are sung to Tanita, the simultaneously virginal and maternal goddess of war, the Moon and female fertility. Flaubert portrays all these scenes in extreme detail, with the perfectionism of a naturalist, while not losing the pathos of a romantic.

Ilze Andresone, curator of the exhibition